Harms from Concentrated Industries: A Primer

I'm happy to share that my new report was published today: Harms from Concentrated Industries: A Primer.

For those of you who have followed my work for a while, the theme of this report will be familiar. Market concentration within sectors and across global value chains has increased in recent years, leading to vast and growing scholarship on the benefits and harms of concentrated industries. The macroeconomic effects of market concentration, and its effects on stakeholders like workers, consumers, and citizens, will significantly impact the achievement of the sustainable development goals. Which is why we've included it under a broader bucket of The Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment's (CCSI) work focused on aligning finance and business with the sustainable development goals. The report can be found at the bottom of this CCSI project page under the "Market Concentration and the SDGs" tab.

"Harms from Concentrated Industries: A Primer" is meant to act as a resource for civil society groups, policy makers, and interested members of the public who would like a basic primer on issues related to market concentration and market power. The document references global and national research across different jurisdictions to demonstrate broad trends. It also lists a number of civil society organizations at the end of the document for readers who wish to find further research and campaign efforts on these issues.

In a short document (25 pages!), it is not feasible to comprehensively cover the range of sector, regional, and political nuances present in this vast body of law and policy. But my hope is this document can act as a short synthesis of broad themes afflicting many global markets today.

Market concentration is difficult to measure, as market definition can be challenging in increasingly complex and globally interconnected supply chains and product and services markets. Additionally, understanding the effects of market concentration, and creating causal links between the rising market shares of dominant firms – and the associated stakeholder harms – can also present challenges.

It is important to note that having market power – in and of itself – is not a bad thing. In fact, it can be beneficial at times for achieving scale – particularly in important industries like energy transmission or highly technical manufacturing processes (like aerospace) that require large CAPEX investments.

Market dominance can come from offering more innovative products, the winner-take-most dynamics of some modern technology markets, network effects, economies of scale or scope, or the increased efficiencies gained from large, globally-interconnected supply chains. Vertical integration throughout supply chains or horizontal dominance through acquiring direct competitors are both methods of acquiring market power.

Many people operate with a theory of change that working to change the largest global companies can have outsized effects on systems. In this view, a company's dominance as supply chain procurers, industry standard-setters, or product innovators positions them to create positive cascading effects throughout the economy.

However, market power can be a double-edged sword, as both the means to acquire it and exercising it can – at times – undermine stakeholder interests. (Extra credit: Michelle Meagher and I wrote about this tension in our paper, Stakeholder Capitalism's Next Frontier: Pro- or Anti-Monopoly?) For example, market power can be gained by thwarting rivals using anti-competitive means like illegal monopolization, using buyer or seller power to underprice rivals (predatory pricing), using unfair or coercive contract terms, by acquiring competitive threats ("killer acquisitions") or a range of other sometimes illegal behavior. This is why antitrust is concerned with abuses of dominant positions or abuses of market power, not just market power itself. When illegal or unfair methods of competition largely define how markets operate, a number of harms to stakeholders emerge.

Our report covers some of these thematic harms from concentrated markets, including:

• Higher Consumer Prices

• Higher Corporate Profit Margins

• Lower Worker’s Wages

• Less Worker and Counterparty Bargaining Power

• Less Innovation

• Less Business Dynamism and Fewer Start-ups

• Lower Growth and Productivity

• Greater Inequality

• Firms Acting as De Facto Private Regulators

• Erosion of Democracy / Democratic Process

• Reinforcement of Western Financial Power

The report also examines globalization and trade, agriculture, and technology and digital markets to explain a few sector and thematic implications in greater detail.

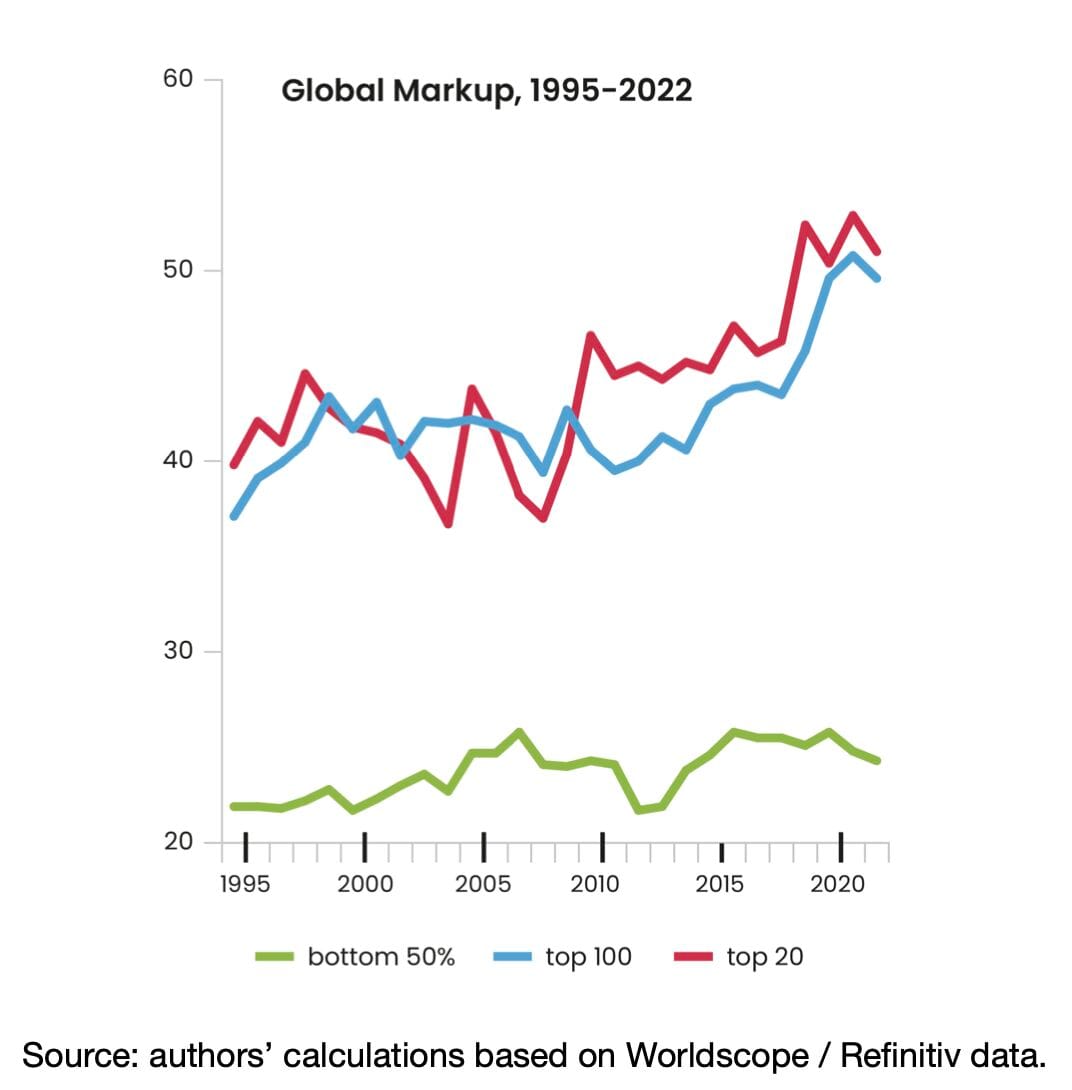

Something I didn't get to include in the report, as it came out after the design was finalized, is new research from the Balanced Economy Project, SOMO, Global Justice Now, and LobbyControl in their report "Taken, not earned: How monopolists drive the world's power and wealth divide." The report has some astounding new data on markups - the difference between what a company charges for a product, vs their marginal production costs:

"Over a five-year period [2017-2022], the average markup for the world's top 20 companies is reported to be 50% compared to 25% average for smaller firms." They say that this is akin to "paying a private tax to billionaires" as consumers.

This data follows other analyses that have shown similar significant rises in markups since the 1980s. For example, Jan De Loecker and Jan Eeckhout found that average markups in the US have risen from 18% in 1980 to 67% in 2017. When firms acquire more market power, they become price setters – and can take advantage of their market position to increase prices without necessarily increasing the quality of a product or service offering. This is one example of stakeholder harm that exercised market power can induce.

I hope you find this primer useful, and will forward to those in your network who could benefit from a resource like this.