Power Play: How Companies are Changing Markets and the Face of Competition

I have an exciting announcement!

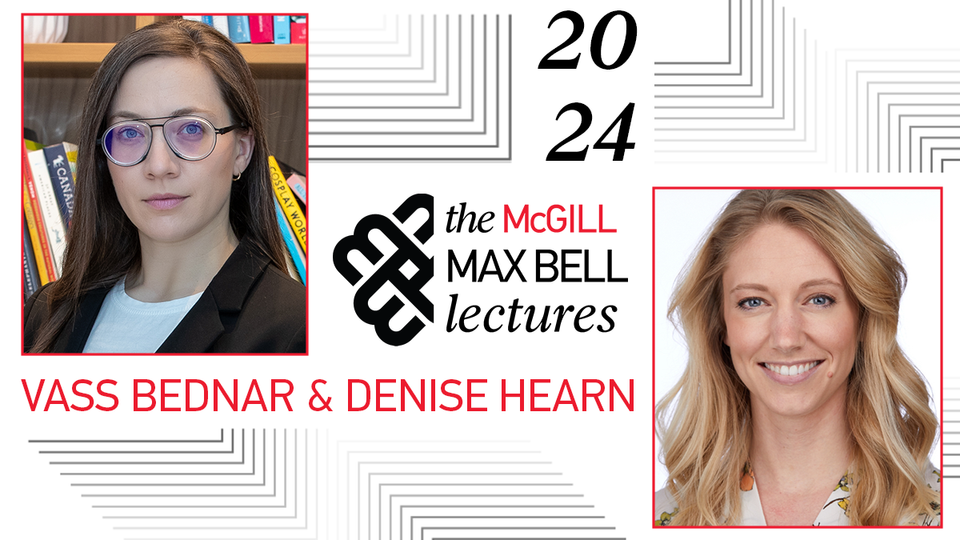

One of my favorite collaborators and dear friends, Vass Bednar, and I have been chosen as McGill University's 2024 Max Bell Public Policy School's authors and lecturers. The book we will co-author, along with an accompanying lecture series, seeks to promote economic ideas for a stronger Canada. Last year's Lecturer was Andrew Leach with his book Between Doom and Denial: Facing Facts about Climate Change.

I am a proud Canadian 🇨🇦 (and, as of last year, also a US citizen 🇺🇸), and think Canada is a special place whose policy and economic victories and challenges can provide lessons for other countries. In this project, we also hope to trace larger lessons about how markets and companies have changed in recent decades, and how our regulatory regimes need to keep pace with this changes – these themes should be globally applicable. More on the book below, in a post co-authored with Vass.

But first, some upcoming events this month:

I'm delivering a Long Now Foundation talk in San Francisco next week, which is a dream-come-true moment for me. It is now sold out (!), but will be live-streamed at this link (Tuesday, Jan 23 at 7pm PT) . Long Now "encourages imagination at the timescale of civilization — the next and last 10,000 years — a timespan we call the long now." It is daunting, humbling, and liberating to try and think at this scale. I'll make my best attempt, as I discuss how our economic stories shape our embodied reality.

Next, I'll be in London for the British Institute of International Comparative Law's Global Antitrust and Sustainability event, sponsored by Freshfields and Frontier Economics. My ongoing work on the intersection of sustainability concerns and antitrust continues via the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment.

It is widely acknowledged that Canada has a competition problem:

- A recent Competition Bureau report found Canada’s competitive intensity in decline;

- Concentration in half of Canadian industries has increased by 40% since 1998 and one-third of Canadian industries saw concentration increase by over 50%;

- Almost 80 per cent of all publicly traded corporations in Canada are controlled by a handful of people; this compares with about 20 percent in the United States. The dynastic family wealth in Canada is largely oligarchic: the Irvings, Westons, Rogers, and Thomson families exert subtle yet profound power in the everyday lives of Canadians;

- Publicly traded Canadian firms in highly concentrated industries have also seen a significant increase in profitability. This is likely driven by firms’ ability to extract higher prices, and not efficiency gains;

- Canadian firms historically under-invest in research and development (“R&D”). It may be that a latent lack of competition means that they simply aren’t compelled to take on the work of actually innovating;

- A recent survey found that most Canadians say we need more competition as it’s too easy for big businesses to take advantage of consumers, and a majority of those surveyed agreed that more competition between businesses will lead to better quality products and more innovation in Canada.

More and more of the economy – from funeral services to movie theatres – is controlled by only a few companies. As a result of this shift, de facto private regulators – in the form of the largest and most powerful corporations – now set market rules and norms outside of more democratic channels. They decide what we buy, how we work, and what the government is able to provide. This lack of market competition hurts workers, consumers, innovation, small businesses, and Canada’s growth prospects.

The economy has changed. But the conversation about competition in Canada hasn’t, really. We’re still obsessively counting the number of competitors in different sectors while ignoring the realities of how markets and companies have evolved over time. We also consistently fail to appreciate the strategic and potentially anti-competitive business tactics that the largest firms often pioneer, which are then mimicked and replicated by smaller players and peers as a means of survival. As these practices diffuse across the economy, enshrining new norms, consumers are worse off.

But, a new movement is emerging, led in part by a stronger, more aggressive Competition Bureau, and in part by concerned citizens realising the importance of competition policy for scaffolding market structure, affecting everything from startup rates, to wages, to high consumer prices, and systems fragility.

Many are hanging their hat on the impending changes to Canada’s competition law, the Competition Act, as the silver bullet to solving our longstanding legal loopholes which have made it difficult for regulators to have much authority. However, markets are public creations, and have guardrails which should be democratically determined. One law is insufficient alone to deal with the complex market realities of the 21st century, including: the financialization of firms, the rise of private equity, digital markets and platforms, artificial intelligence, data pools and privacy, sustainability-related market challenges, and many others.

Competition policy cannot solve all issues, but it is a foundational legal framework that intersects nearly every other legal regime. Our book aims to celebrate the wins we have solidified, while continuing the momentum to tackle the many significant challenges ahead.

Today we are experiencing high levels of income inequality, sticky higher prices even as inflation slows down, low wages, and a host of other economic realities which – in part – find their origin in a lack of robust competition policy enforcement.

Competition policy took a turn in the 1970s and 1980s, attempting to become more ‘neutral’ and ‘scientific’ by elevating the role of economists in adjudicating the law. Complex econometric equations related to calculating market share, anti-competitive harms and benefits, and so on were invented to serve the interest – predominantly – of merging parties. Firms claimed that efficiency gains from mergers and acquisitions would be passed onto consumers through lower prices. But those lower prices largely failed to materialise, as concentrated private power across a range of industries only grew and companies exerted their pricing power. For example, one study in the US showed that when mergers led to six or fewer significant competitors in one industry, prices rose in 95% of cases.

Today, there is a marked turn in policy-making where the neoliberal fantasy that believed liberalised markets would solve allocation problems is eroding. There is now a huge debate about what replaces market fundamentalism, as we watch twin descents into anarchy or authoritarianism in many jurisdictions. The answer, however, lies in democratic liberalism – the fair structuring of markets in a way which undergirds wide prosperity and opportunity for all. Competition policy plays an important role in that restructuring.

The recent removal of the ‘efficiencies defence’ from Canada’s Competition Act articulated in Bill C-56 marks not only a technocratic legislative detail, but a marked shift in approach and philosophy. We no longer see efficiency as the northstar of competition policy in Canada.

Downgrading efficiency as a goal means there is an opportunity for Canada to lead on what competition policy is for – what its aims are – and how it might better serve the interests of all Canadians. Competition for competition’s sake is meaningless, unless it succeeds in delivering the kind of economy we want to live in – not only as consumers, but as workers, business owners, and citizens. It also means that econometric ways of analysing benefits should be better balanced against other goals like systems resiliency, quality jobs, and markets which deliver the best products and services, at reasonable prices, for consumers.

Amending the law is a great initial step, but it’s the first on a long staircase. Now the real work begins to ensure Canada maintains and strengthens its position globally, can provide living wages and decent jobs, and access to markets for innovators to grow and scale their business. Canadians don’t have to be takers of privately-imposed market regulatory regimes. We can collectively determine what markets should mean and do, for us, and set appropriate policies across a range of industries.

We’re eager to continue researching these complex, but critical issues. Some of the questions we are asking ourselves and each other in this process are:

- What are new ways that businesses earn revenue today, including intangible and financialized forms of value?

- How are companies utilising ecosystems of value across multiple “sectors” to reinforce their dominance in markets?

- What other industries – aside from the usual suspects: airlines, telecoms, and banking – should Canadians be worried about in terms of declining competition?

- How can we evolve our legislative and regulatory regimes – not just in competition policy, but across different ministries and areas of law – to align Canada’s economic regime to be more innovative, competitive, and equitable?

- Where can Canada lead and provide inspiration to other jurisdictions?

Occasionally, you’ll see us kicking the tires as we share our thinking in opinion editorials, speeches, panels, and blog posts. We’re always happy to hear your perspectives too - both in terms of diagnosing the problem, and working towards productive solutions.

We thank McGill’s Max Bell School of Public Policy for this opportunity, and look forward to sharing our reflections with you in the fall.

If you'd like to stay updated on this particular project, you can:

• sign up for updates through McGill's Max Bell School of Public Policy

• Subscribe to Vass’s blog, regs to riches