Living Inside Long Time in the Age of Rapid-Fire Chaos

“We exist now in a fleeting bloom of life and knowing, one finger-snap of frantic being, and this is it. This summery burst of life is more bomb than bud. These fecund times are moving fast.” — Samantha Harvey, Orbital

I’ve always had a sense of long time. From a young age, I acutely felt my smallness in a giant universe. It was scary, disorienting, and sad. But also rich with possibility. A good kind of humbling, even if I didn't know it at the time.

Perhaps it was moving every few years internationally, which showed me how big the world truly was, and how small my prior conceptions. Perhaps it was being raised in a religious lineage (Christianity) that defined my present by an alive, multi-generational past and an ever-present future – one which put all things in the context of eternity and cast aspersions on “the things of this world.”

Whatever it was, I couldn’t escape the sense that most of what we get up to in life is a lot of nonsense, with moments of radiant, everlasting meaning. I now have a modified view, which is that the normal, day to day elements of being alive – making and eating food, communing with loved ones, holding a door, observing the world, enjoying being outdoors, meeting someone new, reading, contributing to making the world function, raising children, cleaning, etc., etc. are indeed the most real and “eternal” parts of living. And a lot of the other stuff is still nonsense.

Nevertheless, I’ve been reflecting on long time lately – the notion that we, as a species, have somewhere around 315,000 years as homo sapiens and 6,500 years of human civilization behind us, and some unknown set of years ahead. But even this linear evolution is a blink in the grand story of our cosmos (somewhere between 13.7 and 26.7 billion years old).

It's been helpful to have this long view as all semblances of shared reality, rule of law, and general order melt into oblivion. I hope in sharing these snippets, this perspective may also be helpful to others. A few factors have coalesced to put me in a larger frame at a time of such rapid-fire assaults on our processing abilities.

I’ve been privileged to begin some work with the Long Now Foundation in San Francisco. This nonprofit organization aims to foster long term thinking: “Our work encourages imagination at the timescale of civilization — the next and last 10,000 years —a timespan we call the long now.”

Some of you may remember I gave a talk there last January on how our economic stories shape the world. I’m beyond thrilled to be collaborating with them again.

Over the holidays, I read The Clock of the Long Now: Time and Responsibility, which details the thinking that led to their ambitious vision to build a clock that would run for 10,000 years. In the book, Long Now founder, Stewart Brand, details all the times we have burned entire civilizational libraries. There are many. Typically we burn storehouses of knowledge due to war or religious zealotry. Fires of hubris.

For some odd reason, I found it comforting to reflect on all the times we've torched our greatest civilizational assets (like our collective knowledge, or our hard-built institutional knowledge and processes), only to continue evolving despite periods of extreme darkness and chaos.

We persist.

But we should do everything in our power to prevent and resist these catastrophes, of course.

I’ve also just finished reading Orbital by Samantha Harvey, the winner of the Booker Prize for fiction last year. It details the lives of 6 astronauts and cosmonauts over the course of one day, in their 16 orbits around the earth. Not much happens in the book, and yet everything happens inside that one day – the mundane to the magnificent. The book plays with our sense of time, itself, as the astronauts speed around the world at 17,500 miles per hour, zipping by entire continents in minutes. It only takes 90 minutes to orbit the earth in the International Space Station. And yet life on board the ISS exists in a kind of standstill, a floating capsule of alternate time – fast and slow.

One of the striking facts that book impressed upon me, was that from space, there is hardly any visible evidence of humanity when the sun is shining on it. Our presence is only made known at night with our star burst, circuit board cities. Only a few human-made structures are visible from space with the naked eye during the day, one of which is the Bingham Canyon Mine in Utah, the largest human excavation (!) and deepest open-pit mine in the world. It's apparently a misnomer that you can see the Great Wall of China from space.

And the only visible border, a political scar on an otherwise interconnected and undivided world, is the border between India and Pakistan at night.

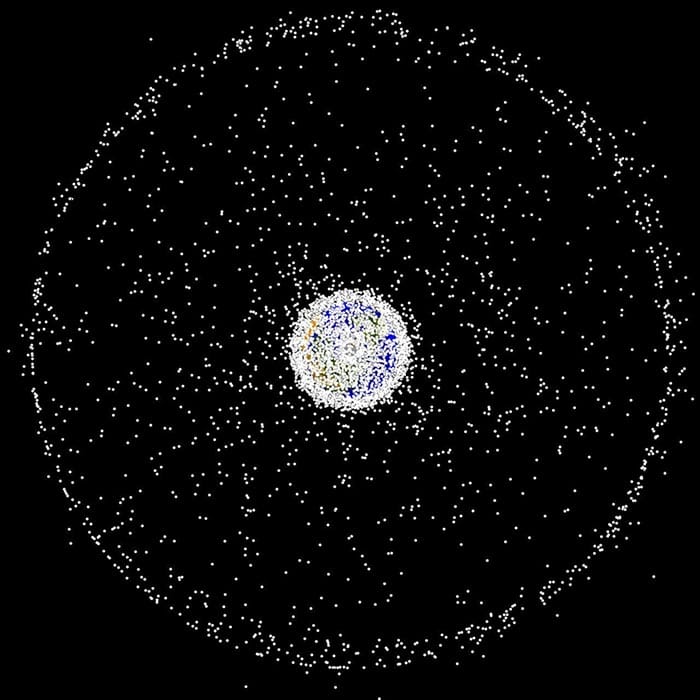

If you were an alternative life form approaching half of the earth in daylight, you may not realize 8 billion humans and many billions more non-human beings inhabit this place. But you'd definitely see the space junk, which would tip you off.

Slightly terrifying number of satellites aside, the book’s brilliance is in its articulation of the paradox of living – the simultaneous meaning and meaninglessness of life.

“Our lives here are inexpressibly trivial and momentous at once. ...Both repetitive and unprecedented. We matter greatly and not at all. To reach some pinnacle of human achievement only to discover that your achievements are next to nothing and that to understand this is the greatest achievement of any life, which itself is nothing, and also much more than everything. Some metal separates us from the void; death is so close. Life is everywhere, everywhere.”

Our lives here are fragile, and short. May we put ourselves in the long arc of time, in the momentary brilliance of our lives, and find our own Work to do. May we live our own questions, remember our place in the wholeness of all things, and let us not be discouraged.

The human story will outlast our borders, our battles, and yes – even our billionaires.