The Downsides of Democratizing Access

Access isn't all it's cracked up to be. The narrative of "democratizing access" is a meme used to convey benefits to consumers while privatizing economic value or building market power for firms acting as gatekeepers. True democratization, however, involves making commons assets accessible to all and sharing economic gains widely.

Today we cover:

• Everyone's democratizing something...

• £8 for 90,000 Spotify plays

• The Downsides of Democratization

• Democratizing Access!™ — the meme

Welcome new subscribers! Here are a few recent posts you may enjoy:

• What Economists can Learn from Starlings

• People + Planet + Profit = Impact?

• Interview with Dark Matter Labs Founder, Indy Johar

And if a friend forwarded you this post, you can subscribe here.

Everyone's democratizing something...

This week, Frontier Airlines and Spirit Airlines announced a $6.6 billion merger to “further democratize air travel” by creating “America’s most competitive ultra-low fare airline.” The combined company will be the fifth largest major US airline, behind American, Delta, United, and Southwest.

I’ve been thinking about how the term ‘democratizing access’ is used repeatedly by companies and investors to denote a kind of vague, generic, and theoretical wide-spread benefit. I did a Neeva search for the phrase “we’re democratizing access to” and page after page of results came back. It turns out — nearly everyone is democratizing access to something.

TokenMaker is democratizing access to the token economy, because “Minting Tokens & NFTs Should Be Easier.” The MIT Media Lab is “Democratizing Access to Space.” Microsoft and Novartis (the Swiss pharmaceutical company) are “Democratizing access to AI” for drug formulations. Purpose Investments is democratizing access to Ether, signalling “a great day for investors.” Mulesoft, a Salesforce company, is democratizing access to data. Membersy is democratizing access to quality, affordable dental care. FarmTogether is democratizing access to farmland, “bringing creative and transformative capital to farming while opening up a vital asset class to all investors.” Impact investors claim to democratize access to credit, or capital, etc. etc.

I could be here all day. You get the point.

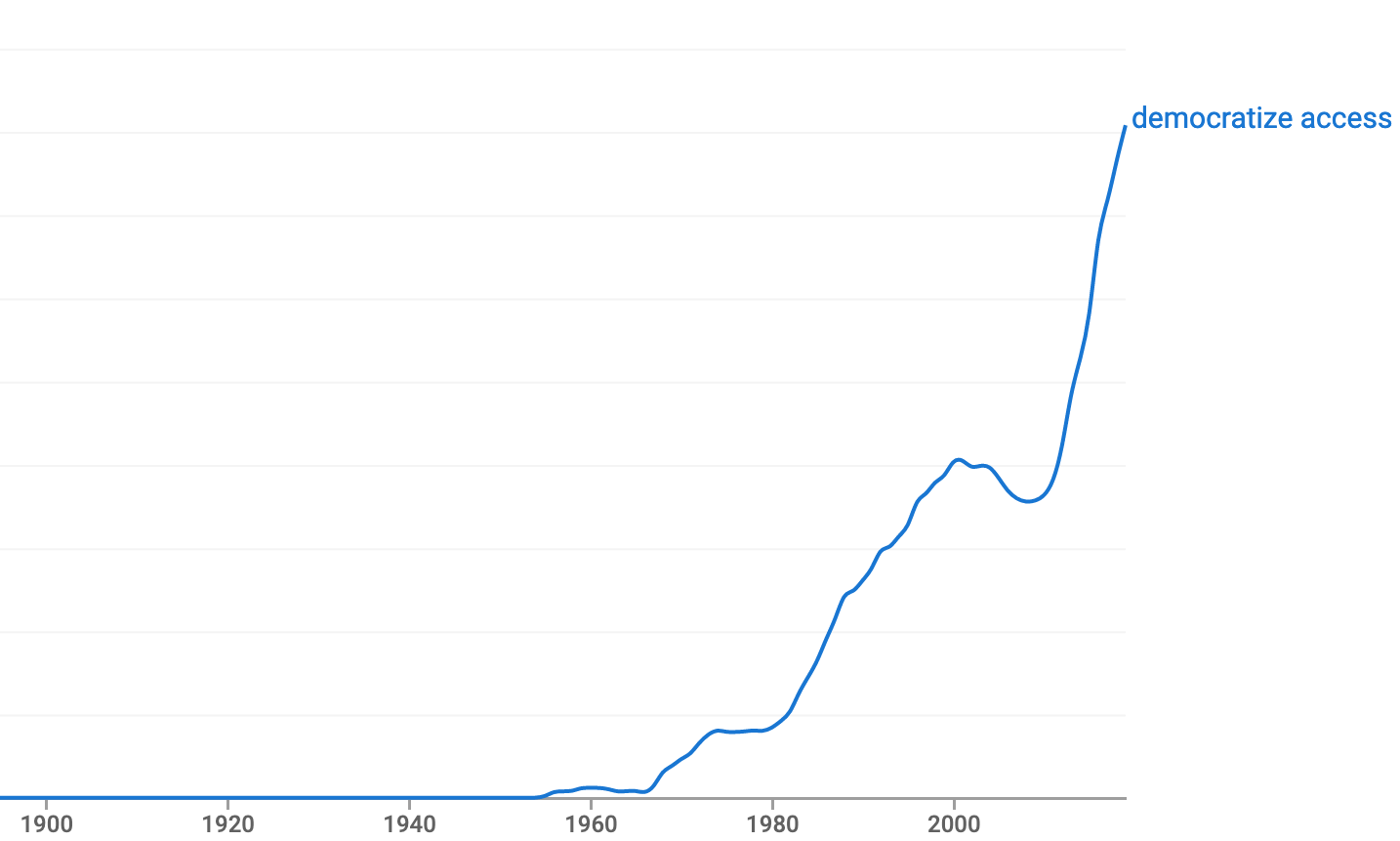

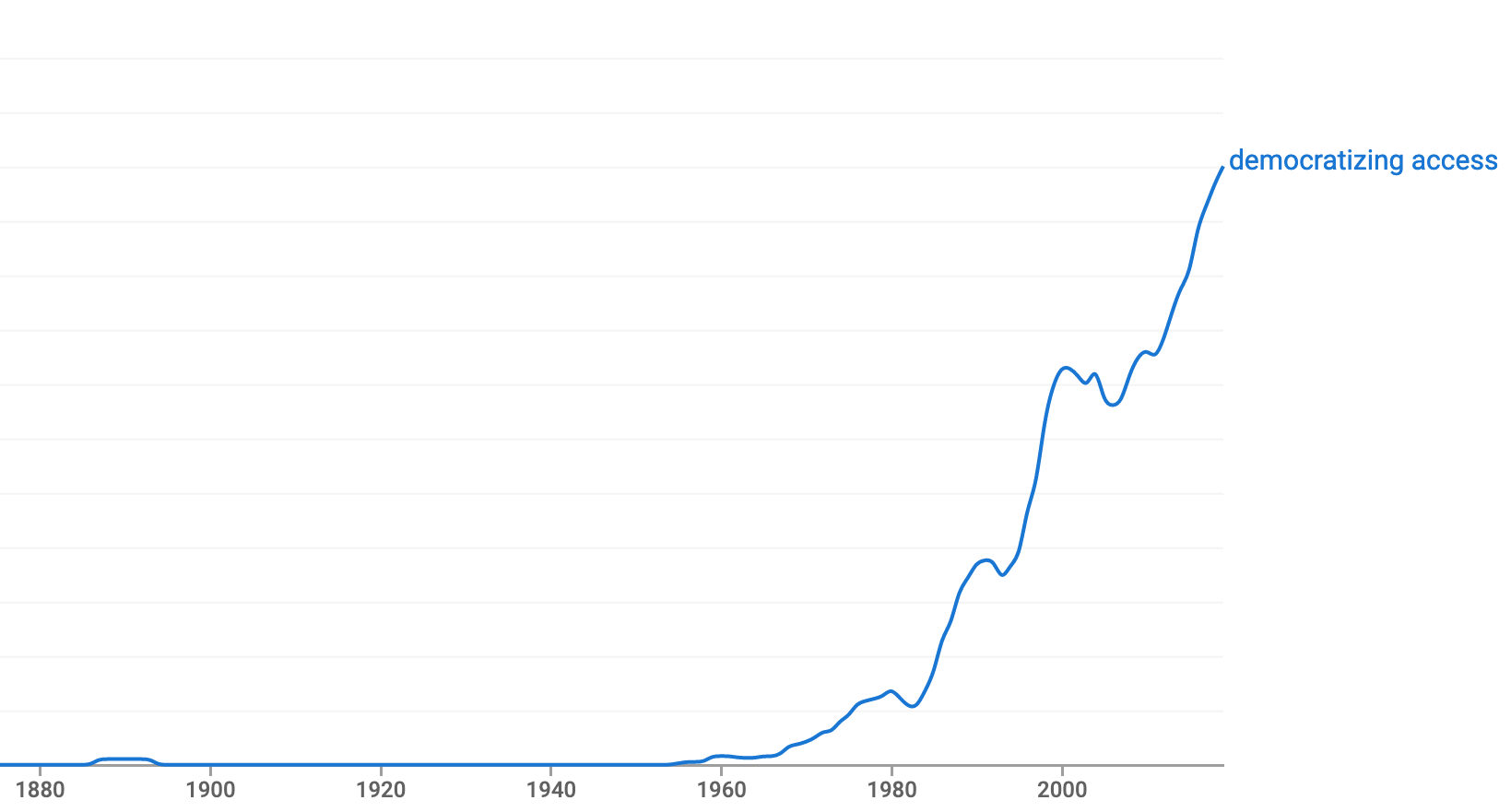

Here are two Google Ngram charts to show the exponential usage of this phrase:

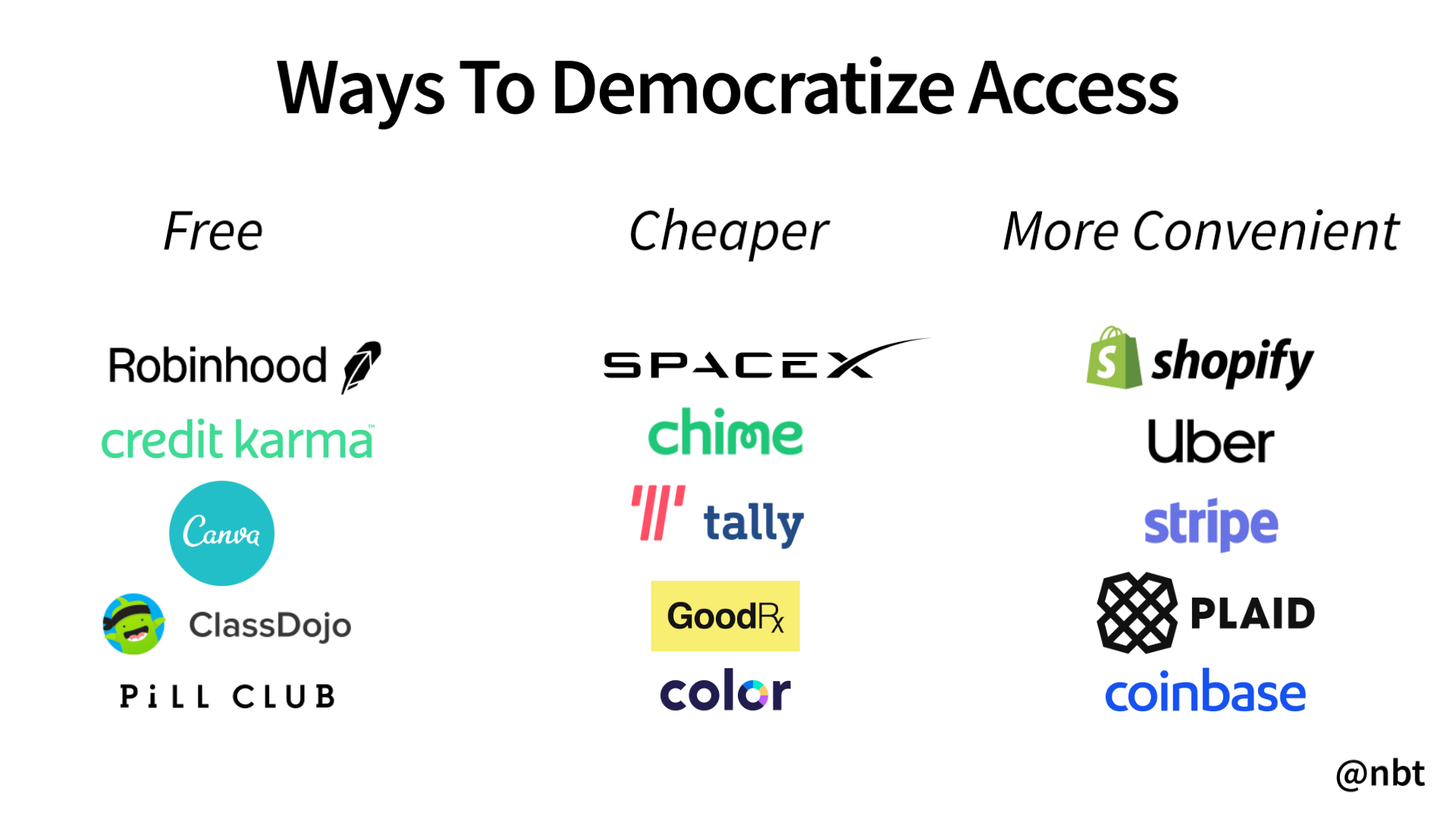

Democratizing access sounds great, and it often can be. According to Silicon Valley venture capitalist Nikhil Basu Trivedi, “There are three types of companies that democratize access to a product or service:

- those that make something that was previously paid now free

- those that make something expensive cheaper

- those that make something hard to use much more convenient”

Free, cheaper, or more convenient are three things I like, and I’m sure you do too. These are, demonstrably good things for consumers — many people can benefit from companies which lower barriers to entry for all kinds of products and services. (This, of course, includes a caveat that many "free" products, as Google and Facebook have well proven, rely on other kinds of value capture).

Democratiziation, therefore, is often used as an investment pitch, or as a glossy marketing phrase — it leaves us in its warm rhetorical glow. Investors can claim lofty, even beneficent, goals of making the world a better place — who doesn’t want more access?

But what if there’s a downside to democratizing access, and in particular, to the narrative of access and how it obscures other power relationships?

Access is very different than ownership or control. Having access to something is not the same as owning it or having an asset that can generate wealth. What if Oprah had said,“You get access to a car and you get access to a car…everybody gets ACCESS TO A CAR!” It just isn’t the same. But this is essentially what Silicon Valley startups and venture capitalists are saying.

Narratives around access to credit or capital, for example, often treat access as the end goal, instead of the beginning of more fundamental questions like: who ultimately controls that access and what economic implications does that pose?

Failing to interrogate these questions often leaves the structure and terms of access unexamined, which may reify existing power dynamics. In some cases, the rhetoric of access can act as a cloak to shroud a company's more nefarious intentions: concentrating asset ownership or market power.

£8 for 90,000 Spotify plays

Take music streaming, for example. During the pandemic, the live music industry was devastated. Live shows are often the best way for artists to make money, as they sell tickets and merchandise. But global shutdown meant that musicians had to rely, almost entirely, on song streaming for income.

In 2018, Daniel Ek, the co-founder and CEO of Spotify said: “Our mission is to unlock the potential of human creativity by giving a million creative artists the opportunity to live off their art and billions of fans the opportunity to enjoy and be inspired by it … We're working to democratize the industry and connect all of us, across the world, in a shared culture that expands our horizons.”

The channels through which consumers access music have largely consolidated into a few major streaming services. There are now 487 million paying music streaming subscribers globally, and Spotify captures 172 million of them (as of Q1 2021). Following behind are Apple Music, Amazon Music, and Tencent.

Despite Ek's claims of 'democratization,' musicians have some choice words for the dominant platform. Many have complained for years about low pay rates for streams. Spotify takes a 30% cut of subscription fees, and the majority of the remaining 70% goes to rights holders including record labels, publishers, and distributors.

By the time money trickles down to artists, they’re often left with infinitesimally small amounts. Artist KT Tunstall stated, “Lockdown has highlighted that streaming splits are just an absolute joke…a monthly $9.99 subscription for all of the music that has ever been made, and your money not even going to the artists you are listening to? It feels like music has been cheapened to a fatal degree.” In the words of another musician, “Got paid £8 for 90,000 plays. F**k Spotify.”

As a Cambridge University Press article states, “corporate rhetoric often assumes there is a tight link between the scale-making ambitions of music streaming platforms on the one hand and the creative empowerment of musicians on the other. Corporate interests and creative interests, in this view, are closely aligned. In practice, however, this link is much looser and more diffuse than emerging literature suggests. Most artists recognise that claims of ‘democratisation’ made by these streaming platforms are deeply flawed and that the unequal power dynamics of the old music industry persist.”

Music streaming is only one example. The above paragraph could be replicated across dozens of industries by simply changing the details. Claims of democratization might make good marketing or sound nice on quarterly earnings calls, but they obscure key questions about how markets are structured and who reaps the benefits. The rhetoric of 'access' often ignores or intentionally papers over power asymmetries in markets — asymmetries companies and investors seek to exploit.

The Downsides of Democratization

- Democratizing access does not democratize ownership or governance structures. And economic value in networks can become highly concentrated over time, despite wide-spread access to products or services.

- Claims of empowerment for stakeholders can cloak existing power structures, including ways in which the new technology or service might reify those power asymmetries:

• For example, one study claims that expectations surrounding equity crowdfunding's ability to democratize entrepreneurial finance do not bear out in reality. Instead, the dismal statistics (due to the bias of investors) which afflict women and non-white founders in attracting venture capital in traditional markets also exist in the so-called ‘democratized’ structure of equity crowdfunding: “Female entrepreneurs do not have higher chances to raise funds in equity crowdfunding. Minority entrepreneurs do not have higher chances of successfully raising capital but attract a higher number of investors.” - Democratization narratives glaze over important questions about the design of new technologies or products— who designed it? Who benefits? Whose worldview and assumptions are embedded in the technology or its structure? Whose data was used in the design process? To whose world are we now being given access to?

- Positioning some companies as arbiters of access (to finance, markets, or other critical infrastructure) is a recipe for gatekeeping behavior. One example is the Apple App store which acts as a gatekeeper between app developers and customers. Only after antitrust scrutiny and pushback from the Coalition for App Fairness, did Apple lower its app purchase commissions from 30% to 15%. More on that in our paper: The Other Red Tape: The Rise of Private Gatekeepers

- Democratization can also lead to homogenization, or reinforce existing cultural biases and preferences (which isn't necessarily democratization's fault, it simply acts as a mirror to our existing biases and they way we've built them into products, services, and their underlying algorithms). Here's a quote from the paper Music, Digitalization, and Democracy:

“The massive upsurge in options that have become available due to digitalization does not necessarily lead to cultural pluralism but, paradoxically, to its opposite…choice overload in culture will make people opt for the same old thing as a way to avoid facing unlimited options, rely on filtering mechanisms rather than on themselves, and become more passive in their participation in cultural life. Thus, there are maybe even growing demands for controlling, or influencing the process of selection and flow in order to democratize music culture in a vibrant and creative way...new media institutions, such as streaming services, have become important gatekeepers with their algorithmic mechanisms that filter available options for the listener.”

Democratizing Access!™ — the meme

To be fair, this is not a post against democratizing access — many times, efforts to do so can bring benefits to a wide array of people. This is, however, an argument against (as Ben Hunt of Epsilon Theory might say) Democratizing Access!™ — a cultural meme with potent narrative power which subverts the original intent of the phrase, idea, technology, or community.1

The literal definition of "democratize" is to make democratic. Making something democratic requires either 1) a form of government in which the people choose leaders by voting or 2) an acknowledgment that all people should be treated equally (I'm paraphrasing Merriam Webster here).

In our case, Democratizing Access!™ has become an abstracted (mostly private-sector) cultural meme which is often used to justify or ignore the consolidation of ownership, power, or control of resources. Impact investors, in particular, should not be duped. But we would all do well to question its validity, whenever the phrase appears.

When I think of truly democratized models which inspire me, they tend to have embedded democratic ownership and/or governance in tandem with the provision of access: the public library, Wikipedia, co-operatives, companies operating under steward-ownership, public transit, the Trust for Public Land, and creative commons licensing, among others...which examples inspire you?

As Web3 creators take up the Democratizing Access narrative, it remains to be seen whether it will be little more than a meme. I hope, for our sake, that it is. In the meantime, we would all do well to remember that democratizing access is not the same as democracy. As the famous Depression-era Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis once said,

"We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can't have both."

1. See Ben Hunt's great post on Bitcoin (the original resistance art project) vs. Bitcoin!™ (the Wall Street and/or central bank abstracted takeover). In Ben's words, "Bitcoin!™ doesn’t stick it to the Man … Bitcoin!™ IS the Man."

Note: Thank you to everyone who continues to shape and inform this blog through conversations, ideas, and discussions. With this issue, I found myself reflecting on conversations I've had with Sandhya Nakhasi, Ryan Glasgo, and Rodney Foxworth (among many others, I'm sure) who challenged and expanded my thinking on the concept of 'access' — thank you.