Probing our Profit Paradigms

Win/win proponents usually cite some version of "People + Planet + Profit = Impact." But what exactly is profit, and how is it derived?

Welcome to those of you who are new subscribers — I am truly delighted you're here! And if a friend forwarded you this post, you can subscribe here. New posts every two(ish) weeks.

Previous posts:

• The Body is Not An Economic Apology

• What is Life? What is Economic Value?

I want to thank Nicholas Poggioli for forwarding me the academic paper which inspired this post. Nicholas does great work investigating the question "How can a company be both profitable and sustainable?” He's on Twitter here.

I try to cover centuries of history in one post today, so if you'd like to skip straight to the cliff notes, the four Profit Regimes are summarized towards the end.

Here's a phrase I recently saw as someone's LinkedIn profile description:

People + Planet + Profit = Impact

Some variation of this phrase regularly appears on company annual reports, investment websites, and consultancy firms. It is the baseline assumption of the majority of stakeholder capitalism proponents and other intellectual frameworks which paved the way: Triple bottom line accounting (which gave name to this rising zeitgeist in the 1990s, but was later recalled by its creator, John Elkington, in 2018), Michael Porter’s Shared Value, ESG investing, sustainable investing, and others. These movements have generally adopted some form of win-win narrative to advance their agendas: What is good for people and the planet, is naturally compatible with profits.

I’ve written elsewhere about the complexities and dangers of win-winism, and more voices are speaking out about its inherent inconsistencies, including its former evangelists, like ex-CIO of Sustainable Investing at BlackRock, Tariq Fancy, and former COO of Timberland, Ken Pucker.

But when I saw this intoxicatingly simple equation on LinkedIn, I became curious about something else…

What is profit, anyway?

Profit seems like such an intuitive and self-evident concept, that we rarely pause to reflect on it. A kind of primordial received wisdom, we assume a collective coherence about what it is. Profit is a little girl’s lemonade stand, which costs $15 in raw materials, sells $35 worth of lemonade cups, and profits $20. Total Revenue – Total Expenses = Profit.

But most accounting is not this simple, nor straightforward.

And even if it were, how is profit derived? Who or what bears the cost of production of those profits (i.e. “externalities”), and what, then, is profit’s ultimate relationship (negative and positive) to “impact?” We will deal with these questions in Part 2 of this series, and Part 3 will suggest ways to reimagine how profits might be defined in the future: How we might move beyond what I’m calling Periscope Profits (narrow views of complex realities) to alternative forms of value measurement and exchange.

In order to tackle the question 'what is profit?' I've enlisted the help of Jonathan Levy at the University of Chicago who has written a fantastic paper on this question: Accounting for Profit and the History of Capital. As Levy traces our evolving conceptions of profit over time, we come to understand that profit is not a constant or self-evident concept whatsoever. In fact, our current way of accounting for profit is very young in the expanse of human commercial time. And in Levy's words, "The history of profit is a history of power."

Levy argues that there have been four distinct “profit regimes” in US history. I’ve renamed the regimes, added other historical context, and interspersed my own reflections below — any errors or mischaracterizations are definitely my fault. Ok, here we go!

Historical Profit Regimes

Regime 1 — Debt ledgers, empire building, and surplus (pre 1850)

Profit, as we conceptualize it today, did not exist prior to the mid 19th century.

Accounting in ancient societies was likely to take the form of credit and debit ledgers — as David Graeber says in his unparalleled book Debt: The First 5000 Years. “For most of human history—at least, the history of states and empires—most human beings have been told that they are debtors.” Indebtedness to someone else, or their indebtedness to you, was the primary method of account for most exchanges. Wealth, usually of kings, emperors, and nobles, was measured in long-range assets like land, or political and militaristic power. “Profit” was not a relevant concept.

When the first global mega-corporations were formed (British East India Company in 1600 and Dutch East India Company in 1602), they were given their license to operate by royal charter and sought to expand the long-range assets of their respective empires. They did this by amassing (stealing) more land, tradeable goods (including people), and political and militaristic power. These companies were granted a monopoly on global trade for the purposes of colonization and empire expansion. The goal was not "profit" per say, but wealth extraction and dominion.

Fast forward to pre-industrial (before 1850) American enterprises. This was the age of local, independent, and often family-owned businesses like stores, farms, and artisan shops. At this time, firms mostly hoped that their income would balance their outgoing goods and expenses: As long as the business owner ended the year without a shortage or outstanding debt, they were happy. Business owners simply tracked their balance of trade.

Prior to the mid 1800s, many firms did not track or report profits. We know this because in the 1830s, the US Federal Government surveyed manufacturing firms to determine their rate of profit. The McLane Report, as it was called, was released in 1833. It showed that half of the survey respondents did not report a rate of profit (because they didn't measure it).

Regime 2 — Cost reduction, child labor, and antitrust (1850-1920)

As the industrial revolution, and subsequent “Progressive Age” kicked into gear, new ideas about corporations emerged. This Gilded Age era saw tycoons like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller amass great industrial empires by using their company’s retained earnings (profits) to invest back into their businesses and build monopolies of steel factories, oil refineries and railroads. In this regime, the operating ratios of firms became paramount, and profit was simply a way to amass more physical assets.

Measuring business costs became increasingly important. Carnegie was obsessed with minimizing costs, figuring that profit would take care of itself if expenses were reduced to a bare minimum. Once quoted as saying,

“Show me your costs sheets. It is more interesting to know how well and how cheaply you have done this thing than how much money you have made, because the one is a temporary result, due possibly to special conditions of trade, but the other means a permanency that will go on with the steel works as long as they last.”

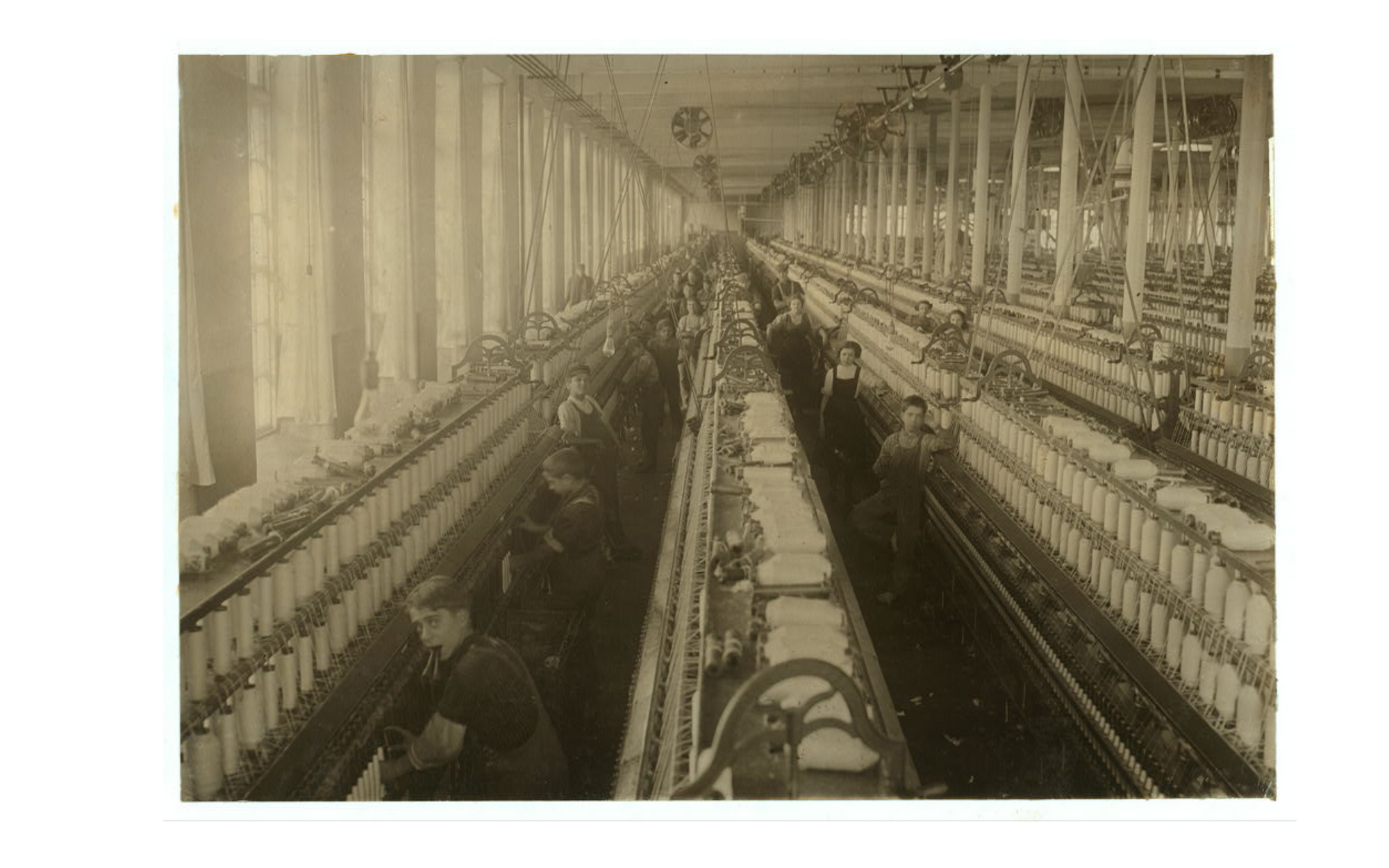

One of the largest input costs was labor, and Carnegie famously squeezed laborers with low pay, long hours (12 hours a day, 7 days a week), and inhumane working conditions. He fought labor unions and collective bargaining, seeing higher wages as a threat to lower input costs for production. Substantive labor reform policies, including child labor laws, were still another decade or two away.

As the “Robber Barons” grew in political power, arguments about the role of the corporation in society reached a crescendo, and the first antitrust laws were passed (The Sherman Act in 1890 and the Clayton Act in 1914).

While philosophical debates about the role of corporations in society waged on, the intellectual idea of a “profit motive” came into being in its infancy. This worldview inculcated the idea that profit was not simply an accounting metric, but an inherent psychological motivation of firms — corporate persons pursued profit as a means to their own ends. Once this idea was established, Levy states, “The profit motive became the foundation of the entire supply and demand edifice of neoclassical economics.”

Today, we are still constrained by the consequences of this idea.

Regime 3 — Multinationals, corporate accountants, and greed is good (1920-1980)

The third regime (1920-80) took the idea of a profit motive and instantiated it into the popular consciousness, making profit an institutional goal unto itself and, later, even synonymous with social benefit.

Following World War II, companies began fanning out across the globe. The following decades saw vast technological advancement, which aided the rise of globalization. Many multinational corporations emerged. In order to keep disparate global offices and corporate divisions cohesive, a new class of corporate managers and accountants was needed to specialize in measuring the company’s varied activities. Levy says, “Profit, in other words, was now a bureaucratic phenomenon.”

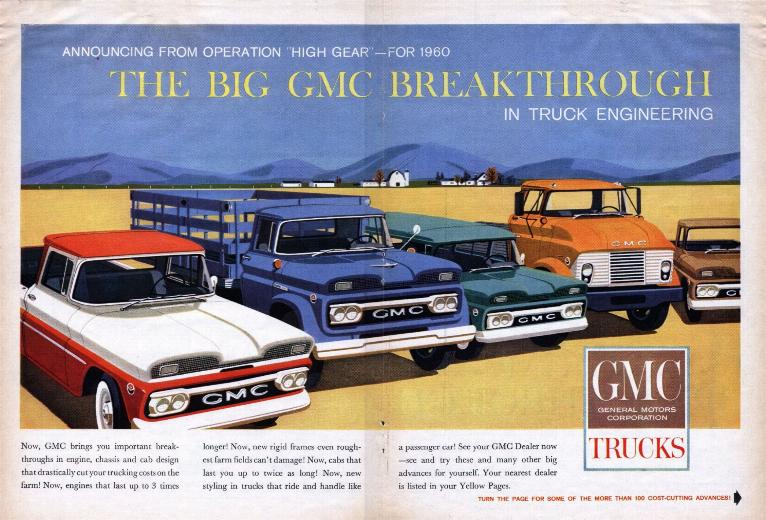

For these new large (mostly) industrial manufacturing firms, the rate of return on invested capital (ROI, as it was known) became a way for new corporate managers to internally measure profits. Because many companies (Ford, GM, Du Pont, and others) required large investments in manufacturing plants, companies would not necessarily get income from their assets for a long period of time. Profit, therefore, was seen as a long-term result of a company’s operations over time.

Corporate accountants looked at the previous ‘sunk costs’ of capital investments (CAPEX) against the current operating ratios of firms. They used historical cost accounting methods to determine profit margins. In simple terms, profits were measured by past activities, not future expectations (as they are today).

But when Milton Friedman penned his infamous 1970 essay, "The Social Responsibility Of Business Is to Increase Its Profits," he built the scaffolding of our current profit paradigm. Alongside Friedman, other Chicago School economists popularized the idea that profit is ultimately good for society — that “the business of business is business.” Greed, in other words, is good.

Regime 4 — It’s better to sell Bitcoin than cars (1980 to present)

Ironically, today's corporations (though given full license to maximize profits by Friedman's doctrine) are largely disinterested in profits.

Our current profit regime (from the 1980s to present day) has been irreversibly changed by the financialization of companies. Firms now use complex financing instruments, including derivatives, to adjust the assets and liabilities on their balance sheets. Corporate accountants adopted ‘mark to market’ or ‘fair value’ accounting methods during this period — the value of a company’s assets is based on what it could be exchanged for in the market, right now. This, then, gets reflected in a company’s stock price.

Today, companies can earn 'profits' simply by re-arranging the financial assets on their balance sheet, instead of by providing high quality goods and services. As my friend and collaborator Taylor Sekhon recently said to me, "corporations are no longer companies that invest, they are investment companies."

The best example of this, perhaps, is Tesla. The company had a record quarter this past April (followed by another record in Q3), but it didn’t post those profits by selling cars. The company’s soaring profits were mostly a result of selling Bitcoin and regulatory credits. Charley Grant for the WSJ:

“The company said that it sold some of the $1.5 billion worth of bitcoin that it purchased in February, contributing $101 million to the bottom line. That is nearly a fourth of its total profit. What is more, sales of regulatory credits to other auto makers to help them meet emissions mandates, which carry a 100% profit margin, reached $518 million. That accounts for nearly 100% of Tesla’s $533 million in pretax income. Those two helping hands helped avert red ink.”

Firms now can manipulate market pricing and valuations as a way to earn virtual 'profits' instead of selling real goods and services. In some cases, profits are not even a prerequisite for high valuations. In 2020, 80% of firms that went public (IPOed) had negative earnings...

In conjunction with financialization, the rise of the knowledge and data economies led to the “asset light” corporation, which also moved manufacturing capacity abroad, invested heavily in intellectual property protection instead of physical assets or CAPEX spending, and offshored labor to low-wage economies globally.

These, and other dynamics we'll explore in Part 2, created a corporation that decoupled profit from productive investment. As Julius Krein states in a recent American Affairs piece (which I highly recommend):

"Today’s shareholder-driven corporations are not necessarily—or even primarily—motivated to engage in the traditional methods of “growing a business.” Companies are often highly incentivized to pursue financial engineering and valuation multiple expansion, rather than investing to increase earnings."

Four Profit Regimes Summary:

Regime 1: Debt ledgers, empire building, and surplus (pre 1850)

Profit, as we conceptualize it today, was not actively tracked by the majority of firms prior to ~1850. In ancient societies, profit was a moot point because wealth was held in land and stockpiles of valuable goods.

Regime 2: Cost reduction, child labor, and antitrust (1850-1920)

Lowering input costs (expenses) was the primary concern by industrialists and was seen as the best way to boost profits. Profits tended to be reinvested in additional manufacturing plants and factories, railroad expansions, or steam engines as the Robber Barrons built great industrial empires, controlling the infrastructure of commerce.

Regime 3: Multinationals, corporate accountants, and greed is good (1920-1980)

Corporate accountants are needed to tame the growing, global beast — the multinational corporation. Profit is mostly an internal metric that helps makes sense of diverse and dispersed corporate activities. Milton Friedman puts his ideas to paper and legitimizes the notion that greed (profit maximization) is a societal good.

Regime 4: It’s better to sell Bitcoin than cars (1980 to present)

Profit is whatever a firm can sell its assets for in the market, right now. Increasingly, those assets are financial — like Bitcoin or complex derivatives — which makes virtual profit somewhat untethered from the productive investment of firms.

Profit — a matter of perception

All this is to say that profit is not a foregone conclusion, or even a straight-forward concept. Even today, measuring corporate profits is an exercise in many pedantic accounting decisions. How should we value a company's assets, the majority of which are now intangible and financial?

How we understand and account for profit has major implications on the shape of markets. Our paradigms shape our systems and the goals we pursue. Profit paradigms are no different. Jonathan Levy, one final time, to close us out:

“Profit paradigms have the power to alter the structural conditions of capitalism, I hope to demonstrate, as they themselves emerge from the structural possibilities at stake in any given moment of capitalism’s history, given the particular concrete forms of capital, as well as the cognitive orientations that make profiting from them possible...

Today, the future of profit, the future history of capital, is very much up for grabs.”

Stay tuned for Part 2 of this series, where we’ll look at the various ways corporate profits are made today (including the good, the bad, and the downright strange). Ideally this helps tease out a more cogent and nuanced conversation than the over-simplified People + Planet + Profits = Impact equation.