ESG’s Many Sharpshooters

“No word matters. But man forgets reality and remembers words.”

– Roger Zelazny, author of Lord of Light

Today’s proxy ESG (environmental, social, governance) wars choose narrative over reality, on both the left and the right.

This week, President Biden used his veto power for the first time to block an anti-ESG bill by House Republicans. The bill sought to roll-back a Department of Labor rule which allowed investment managers of government pension funds to consider relevant ESG-related information like climate change, worker treatment, or legal risks. Republicans wanted managers to focus only on investment returns to maximize pensioner savings. Last week, BlackRock’s Larry Fink released his annual investor letter, and the three letters “ESG” were conspicuously absent.

I just vetoed my first bill.

— President Biden (@POTUS) March 20, 2023

This bill would risk your retirement savings by making it illegal to consider risk factors MAGA House Republicans don't like.

Your plan manager should be able to protect your hard-earned savings — whether Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene likes it or not. pic.twitter.com/PxuoJBdEee

ESG is many things to many people.

If you’re a pension fund trustee, ESG may be a way of analyzing systemic risks – like climate change or governance issues at portfolio companies – which you believe have a material impact on financial returns. If you’re a Republican with an anti-woke capitalism agenda, ESG is evil incarnate – a ploy to use the power of dominant financial companies to impose an undemocratic leftist agenda.

If you’re an asset manager with a sprawling universe of passive index funds, ESG is a convenient marketing gimmick to charge more for largely undifferentiated S&P 500 trackers. And if you’re a consumer, you may think that ESG is a way of doing well by doing good – investing your money in more sustainable companies that have a hope of taming the worst extractions of capitalism.

The problem, of course, is that ESG can be whatever someone wants it to be.

The best metaphor I can find for ESG is the Texas sharpshooter. In this fallacy, a man haphazardly shoots the side of a barn and then draws a bullseye around each of his bullet holes. He then invites the neighbors over to see what a great marksman he is, and they conclude he is the best in the state. Of course, their reasoning is fallacious, because the data was selectively chosen and made to signal consistency where there was really only randomness, chaos, and very creative marketing.

A lack of standardized metrics for ESG has been a long recognized problem for practitioners. The myriad definitions of ESG makes it increasingly meaningless to talk about ESG outperformance, ESG inflows, or ESG alpha in a way that tells us much about what is happening.

In a soon to be released paper, "ESG is Everything and Nothing at All: What 1,000 Different Definitions of Environmental, Social and Governance Investing, Scoring, and Conceptual Frameworks Tell Us" Jason Miklian and John E. Katsos examine the proliferation of ESG definitions, not only among businesses, policymakers, and consultants but also among scholars.

It's 1000 sharpshooters with 1000 bullseyes.

This lack of clarity has turned ESG into a target on all sides. Some progressives worry that ESG has conflated the pursuit of investment returns with investments in the real economy that are needed to truly achieve sustainability. Dissenters like Ken Pucker, former COO of Timberland, and Tariq Fancy, former Chief Investment Officer for Sustainable Investing at BlackRock, emphasize that most ESG ratings measure the risks that planetary breakdown (both social and environmental) pose to a company’s returns, not the other way around.

Conservatives worry that ESG is a pernicious strategy “because it allows the left to accomplish what it could never hope to achieve at the ballot box,” according to Mike Pence. They claim that companies have amassed too much power to set the cultural agenda – one in which “leftist” values are expressed, not through the political process, but through powerful firms, their leaders, and their financiers.

Both are correct.

Conservatives have correctly identified that large financiers are now profound shapers of corporate governance and political allocation, although their critique ignores decades of their own party’s deregulatory agenda which curtailed the state’s countervailing power and weakened laws designed to reign in dominant corporations.

The “Big Three” asset managers —BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street— now manage over $22 trillion in combined assets, and are in the anti-ESG crosshairs. 82% of all assets flowing into all investment funds—both active and “passive”—over the last decade have gone to the Big Three, and on average the Big Three own 22% of the typical S&P 500 company. By October of last year, Republican state treasurers had pulled $1 billion of assets from BlackRock, citing ESG concerns.

And although BlackRock’s Larry Fink makes for a good boogeyman, the company’s political agenda is overstated. Research has shown that index providers vote in line with corporate management 90% of the time, meaning they don’t exert much of an additional political agenda beyond what companies are already pursuing. And the index providers remain some of the largest financiers of fossil fuel industries.

Asset managers like BlackRock are incentivized to gather assets from institutional owners and retail investors, as their revenue comes from fee generation on total assets under management. Despite their high degree of ownership of companies, asset managers are not necessarily incentivized to produce returns from any one company within their sprawling universe of passive index funds, but rather to maximize market returns. And because they own such large percentages of companies, exiting or divesting from companies completely is not an option.

As the researcher Ben Braun puts it, “Asset managers’ corporate governance policies are subservient to the — increasingly inconsistent — goals of maximizing assets under management while avoiding regulatory backlash. Unlike exit-based power, control-based power is constrained by being highly visible and, therefore, easily politicized.”

The progressive ESG dissenters are also correct.

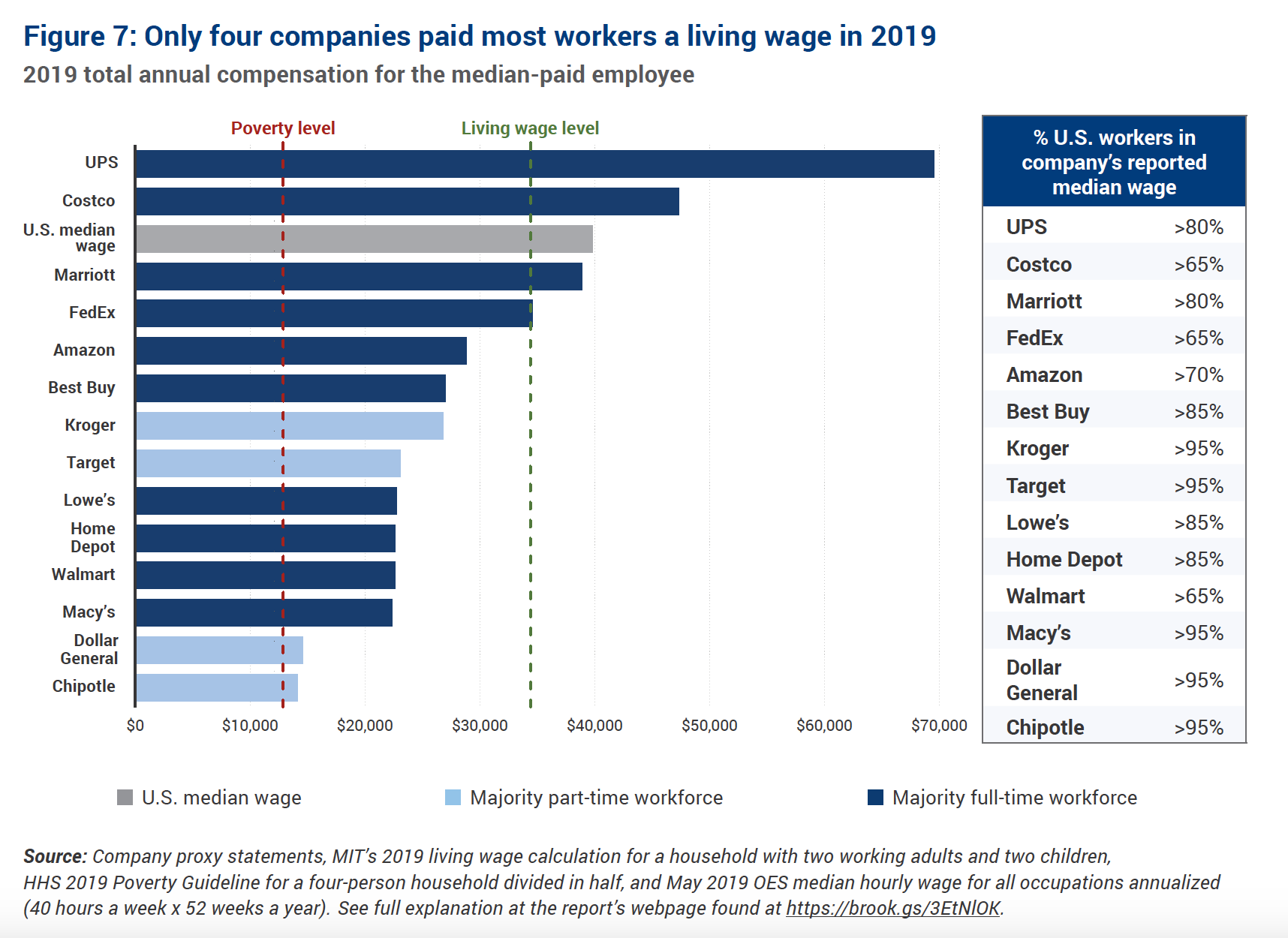

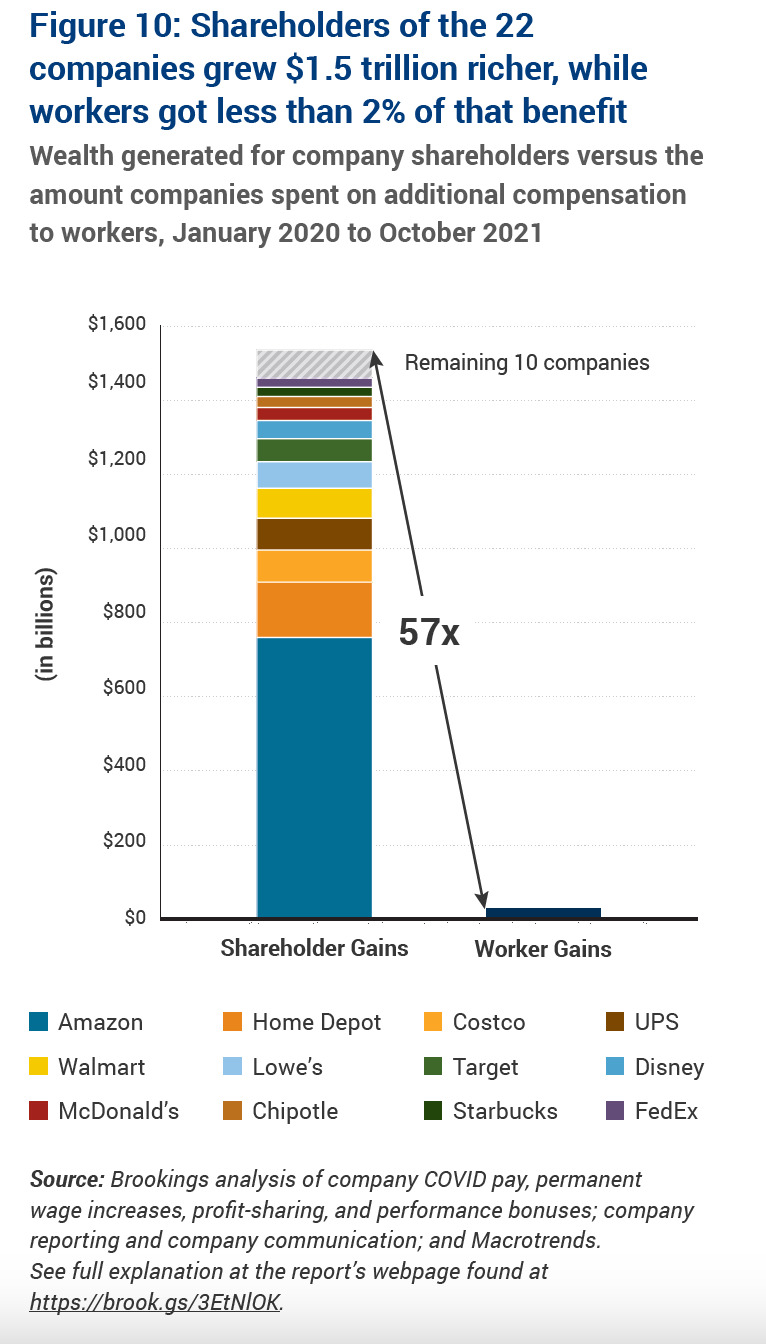

Despite its emphasis on the environment and worker’s rights, the bullseye of ESG investing (and its cousin, stakeholder capitalism) is, at the end of the day, still profits. One example: the Federal Trade Commission recently proposed a rule to ban noncompetes across the country, estimating that this would bolster worker’s wages by an astounding $300 billion a year due to increased bargaining power. The Chamber of Commerce strongly opposes the rule, and groups like the Business Roundtable and JUST Capital remain quiet. Research has shown that many companies which signed the BRT stakeholder capitalism statement on corporate purpose actually paid workers less during the pandemic than companies which did not sign.

Like all constructed narratives, ESG is a product of the bullet, the barn, and the marksman in focus. As it increasingly becomes a target, utilized as a boogeyman for political purposes, its multi-layered logical fallacies will only come further undone.

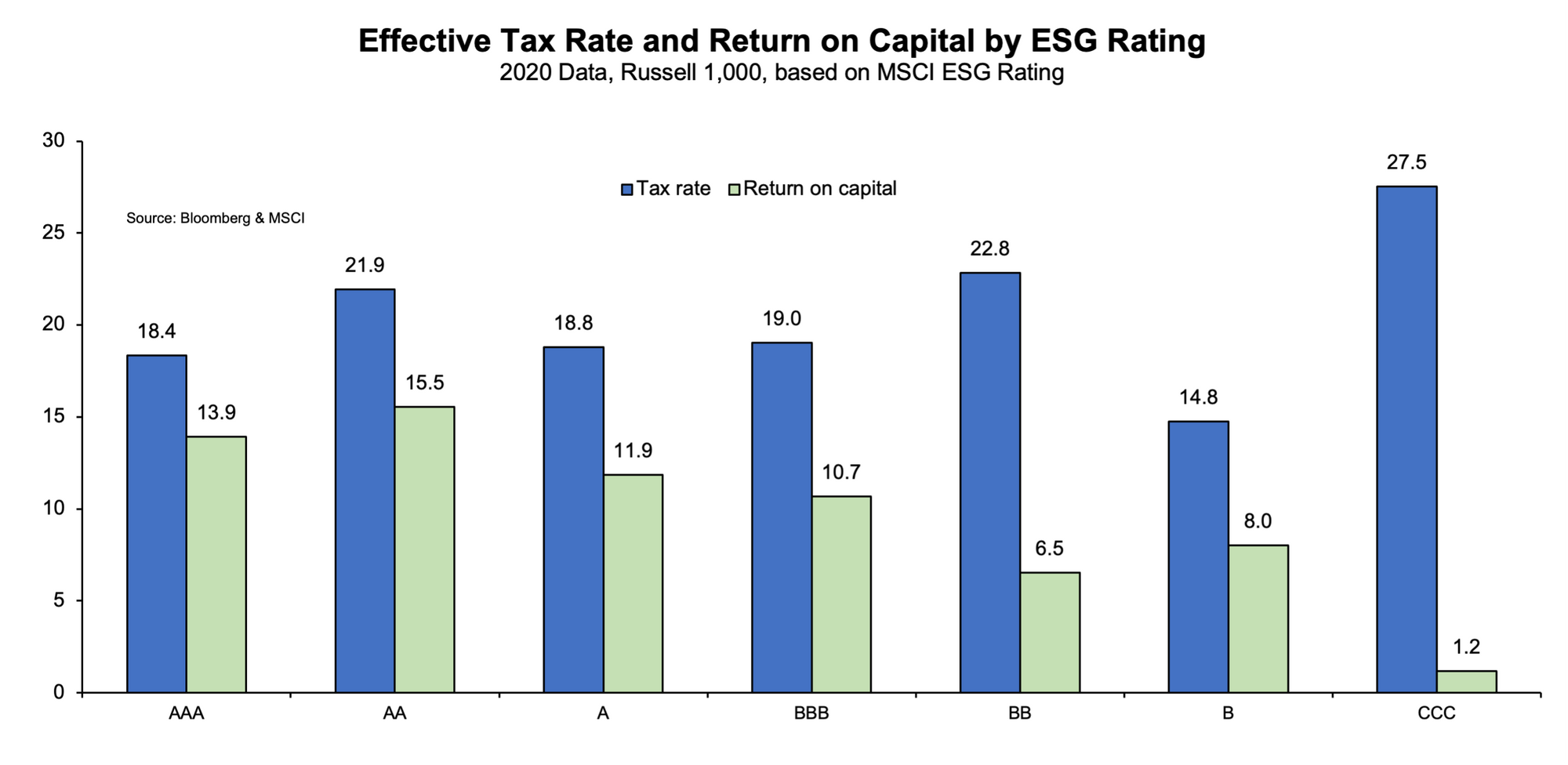

Investors who care about systemic risks would do well to focus on the real issues at hand: First, the rampant political lobbying which undermines democratic functioning and the erosion of the state’s countervailing power against concentrated corporate and financial power. Second, corporate tax evasion.There is an inverse relationship between a corporation’s ESG rating and their effective tax rate – the higher a company’s ESG rating, the lower its effective tax rate. And third, the incredible rise in contractual work – and coercive contract terms like noncompetes – that exacerbate worker precarity. Alphabet, the number one held ESG company in 2022 and ranked the top “just” US company according to JUST Capital, hires more contract workers than full time employees.

The breakdown of the ESG narrative is an opportunity. People of all political affiliations must rethink the relationship between corporations, democracy, and true stakeholder welfare, and asset owners must pursue real economy investments that will generate true sustainability gains. Perhaps it allows us to refocus our aim – and take the real shots necessary to bring our planet back from the brink.