New Report – Sustainability and Antitrust: A Landscape Analysis

Hello readers,

First, a personal update: After 3 fantastic years as a part-time Senior Fellow at the American Economic Liberties Project, I am transitioning to be an informal Senior Advisor. I learned a tremendous amount from my brilliant colleagues, and am proud of the research and projects the team pioneered and the work I supported while there. You can find some of the reports I co-authored here. My last hurrah at AELP was helping co-organize the Anti-Monopoly Summit with one of my heroes, Nidhi Hegde (AELP's Managing Director). The Summit was a huge success and a marquee day for the US anti-monopoly movement. We had over 300 attendees in person and more than 9,000 watching online. You can read the recap blog here and watch a special message from President Biden.

I'm excited to share that I am now a Senior Fellow at the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment, part of Columbia University's Climate School, and am co-leading our Antitrust and Sustainability project – which is what today's newsletter is all about!

This month, Congress has held both ‘anti-ESG’ hearings and has brought Lina Khan, the Chair of the Federal Trade Commission, to testify in an effort to undermine her stronger approach to antitrust enforcement. The intersection of ESG and financial risk management issues, sustainability concerns, and antitrust principles is increasingly confused, and therefore it is increasingly critical to separate narrative fiction from legal reality. Our new report aims to do just that.

About a year ago, I became interested in the intersection of antitrust and sustainability – how do we, as a species, learn to live within our planetary boundaries while maintaining the social floors all humans need to live with dignity and security (access to food, water, shelter, healthcare and more)? What does antitrust law and competition policy – profound shapers of market structure and economic allocation – have to say about this, if anything? And within the opportunities and constraints of a market-based economy, what role does competition or collaboration among private companies have to play in reaching these objectives? What about the market power of dominant firms? Turns out, these are very challenging and complex questions and many smart people disagree on fundamentals.

Myself and my co-authors Lisa Sachs, Director of the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment (CCSI), and Cynthia Hanawalt, Senior Fellow at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, try to unpack these questions in the report we're releasing today: Antitrust and Sustainability: A Landscape Analysis. The report gives an overview of the broad purview of antitrust law, and the myriad and complex ways in which it intersects with and affects sustainability goals.

Some business groups have claimed that antitrust is at odds with sustainability goals because of its focus on competition, lowering consumer prices, and maximizing output. They argue that these goals are fundamentally in tension with sustainability principles of reducing output and consumption (degrowth), and internalizing previously 'externalized costs' of production which could entail consumers paying higher prices for goods and services.

Companies are facing increased pressure to address sustainability issues, from both shareholders and the public. But it's not enough to change a few board seats at ExxonMobil, you need the entire sector to commit to more sustainable practices to have any effect. Industry-wide standards-setting or collaborations are nothing new, and antitrust law across many different jurisdictions has guidelines for what kinds of competitor collaborations are permissible (pro-social or benign) and which are not. While collaboration naturally sounds like a good thing, it can also be anti-social when companies coordinate as cartels or in anti-competitive ways which harm the public. As Adam Smith said in The Wealth of Nations,

"People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.”

Competition agencies, since their inception, have wrestled with how to define what constitutes pro-social coordination, and how to measure any anti-competitive harms against other social and economic benefits.

These questions, though they sound academic, are critical. Within the past year, antitrust language and concepts have been weaponized to undermine private-sector collaboration on climate initiatives. For example, financial sector climate alliances and other investor coalitions have been accused of boycotting fossil fuel companies, in violation of antitrust principles. And state-level anti-ESG bills have similarly employed “boycott” language in ways that would not be considered antitrust boycotts under traditional legal principles.

Because of this, antitrust-related questions and challenges are said to be chilling necessary engagement and mobilization of private actors to address climate change and other sustainability-related challenges.

For example, the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) – the world's largest business association and lobbying group – released a report in 2022 claiming that antitrust / competition policy was getting in the way of climate action. They claim that there is a "disastrous inconsistency between the imperative of fighting climate change and competition law or policy." Their report, "When Chilling Contributes to Warming" puts it this way:

"As frequently occurs, when regulation lags behind in driving and promoting change, the private sector has stepped forward and taken action. Rising sustainability concerns have created increasing pressure on businesses to make environment-friendly investments, innovations and purchasing decisions...When all, or most, competitors move together and in the same direction, change will occur. What if such change benefits the environment and society, but at the cost of temporarily reducing competition? How much of a reduction of competition are we ready to accept?"

While policy can be slow-moving, the ICC claim ignores the ways in which corporate political spending, lobbying, and revolving door dynamics may undermine or forestall regulator’s attempts to bring forward comprehensive reforms. For example, a recent report found a positive correlation between market power and lobbying spend – the more market power a corporation acquires, the more it lobbies. The results suggested a “significant empirical link between increased corporate consolidation and increased corporate political power.”

The ICC report recommends that competition policy regulators provide updated guidelines for businesses which give wider latitude for sustainability-related collaboration among competing firms or firms in the same industry. Many agencies, including the EU Commission, the UK's Competition and Markets Authority, and others have issued updated guidelines with sustainability-related exemptions. It remains to be seen whether these relaxed guidelines will yield sustainability benefits, as firms are promising. A concern / theory I have is that ‘sustainability gains’ are now becoming the new ‘efficiency gains’ that companies propose as deserving of new regulatory or legislative carve outs. And efficiency gains, which were supposed to be passed onto consumers by way of lower prices, have largely been illusory or overstated.

So while much of the "green antitrust" conversation has focused on firm collaborations, there are two problems with this:

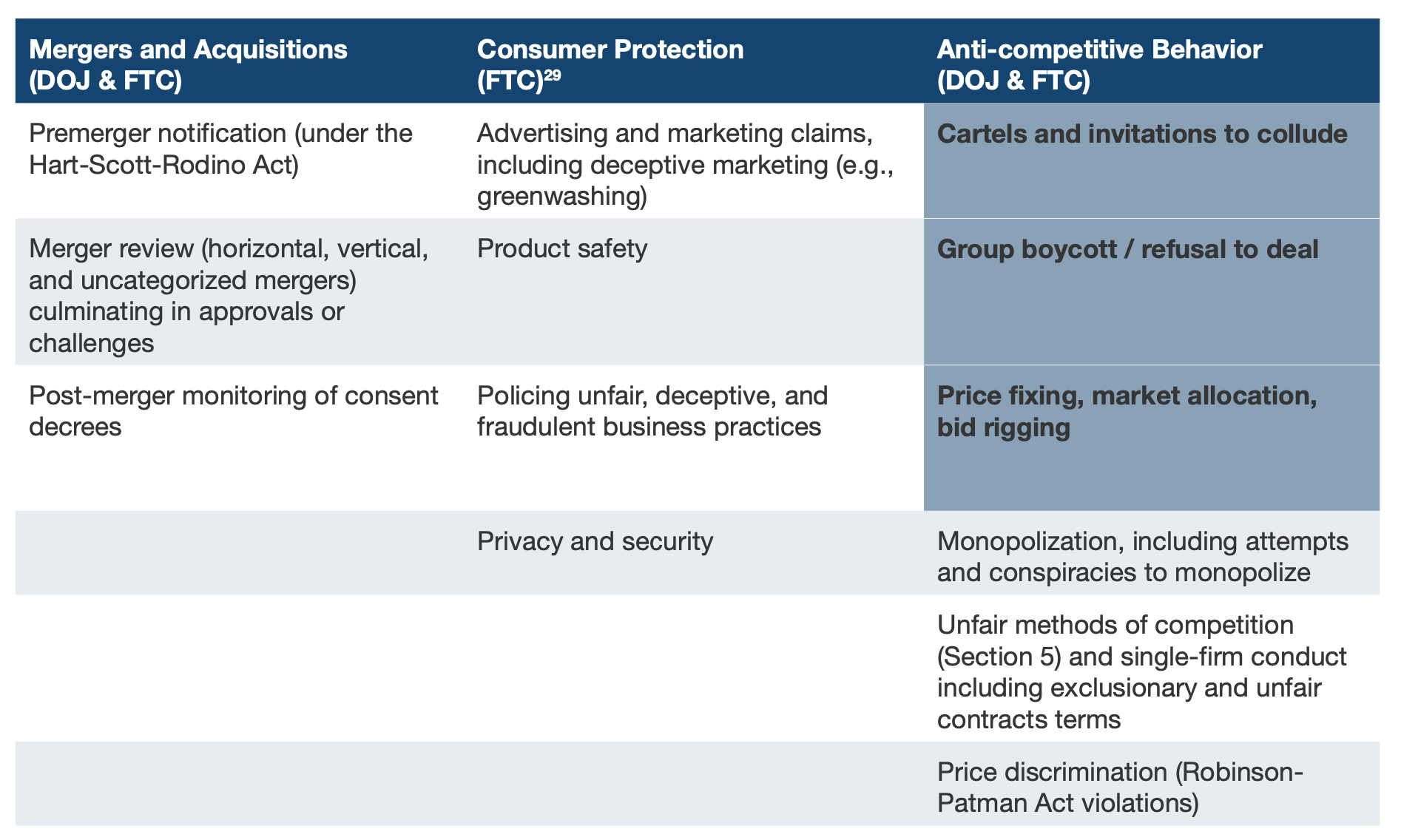

First, this is only a small portion of competition agency's remits (as shown in the chart below for the US DOJ and FTC). Our paper focuses mostly on competitor collaborations, but merger policy and consumer protection are arguably stronger and more effective tools for addressing sustainability concerns through competition agencies. The dark blue shading under anti-competitive behavior shows where competitor collaboration concerns emerge for agencies.

Secondly, it assumes that large firms should be given special legal accommodation to coordinate, when other economic agents (workers, consumers, etc.) should not.

The big questions antitrust law seeks to answer are: who should be allowed to coordinate in markets? For what purposes? And in whose benefit? Professor Sunjukta Paul's paper, "Antitrust As Allocator of Coordination Rights" was foundational for me in thinking about these questions. As Paul notes,

"Practically speaking, the reigning antitrust paradigm authorizes large, powerful firms as the primary mechanisms of economic and market coordination, while largely undermining others: from workers’ organizations to small business cooperation to democratic regulation of markets. While deploying the legal concept of competition to undermine disfavored forms of economic coordination, antitrust law also quietly underwrites certain major exceptions to principles of competition, notably, the business firm itself."

Large corporations have been analogized to keystone species, in that their role in affecting change through their respective industries can cascade throughout

the supply chain. Some believe that working with dominant firms on climate or social goals is the fastest and most efficient way to make progress. In this view, larger firms with more capital are better positioned to invest in green technology or sustainability initiatives, and that when large firms address their own negative impacts through their operations and supply chains, the effects can be substantial. It may also be the case that large, multinational firms are better equipped to deal with corruption issues or low social and environmental standards in foreign countries.

In contrast, others believe that increased competition – and challenges to dominant incumbents – produces the necessary firm incentives to innovate and invest in sustainability-related initiatives. Some research has shown that market concentration proxies are negatively related to widely used corporate social responsibility (CSR) measures, and that firms in more competitive industries have a superior environmental performance, as measured by firm pollution levels.

In recent years, various movements aimed at harnessing the power of large firms have gained steam: sustainable finance, ESG risk management, stakeholder capitalism, and responsible corporate governance, among others. Most of these movements have a theory of change that pressuring or using the power of the largest and most powerful firms is the clearest path to progress.

But the larger question to keep in mind is: Who should be allowed to collaborate to set market terms?

- Shareholders and shareholder coalitions?

- Companies in the same industry (via industry associations)?

- Firms that directly compete? (competitor collaborations?)

- Workers? Independent contractors?

- Small and medium-sized businesses?

- Regulators (both domestic and international)?

The emergence of stakeholder capitalism, universal ownership theory, a rising labor movement, and the anti-ESG backlash have challenged the corporation and its role in society. Each movement asserts its own theory of societal organization, and whose stakeholder interests (and coordinated demands) should be foregrounded.

For example, proponents of universal ownership theory argue that shareholders and shareholder coalitions should have special antitrust accommodation to coordinate on ESG issues which affect their long-term returns. This is in direct conflict with antitrust's prohibition on horizontal shareholding – in which companies with the same owner tacitly collude – not to compete with one another, but to make the industry overall do well. Martin Schmalz at Oxford has done great work on this, and this 7 minute video helps explain this concept well. There's even a cameo of Richard Branson dressed as a flight attendant in red lipstick.

But it's not just shareholders that want to coordinate. Companies in the same industry, or direct competitors, claim a desire to coordinate on sustainability projects and goals (like circular economy initiatives or net zero targets), already receiving special accommodation from many European and Asian antitrust agencies. An uptick in labor organizing in 2022, amidst a longstanding decline in unionization in the US, signals a rising labor movement trying to reassert its right to coordination rights.

Even US federal antitrust enforcers are seeking greater levels of cooperation both domestically and internationally. The DOJ and FTC have signed new memorandums of understanding with other federal agencies with antitrust authority, and a June 2023 public comment period asks for input on how the FTC can better coordinate on cases with state Attorneys General. At the international level, the FTC and DOJ have come under fire from the Chamber of Commerce for coordinating with other international competition agencies on “big tech” merger cases.

So the question of whose coorodination rights should be accommodated is central to questions of sustainability and antitrust. The second fundamental question is: what should competition policy aim to do? What goal or goals should it prioritize?

Global Antitrust Renaissance

Antitrust and competition policy are in a moment of Renaissance, not only in the strength of enforcement globally, but also within fierce academic and practitioner debates about how to reconstitute this policy field to meet 21st century challenges.

Sustainability is just one of many market changes driving antitrust reconsiderations. New market realities are re-shuffling long-held antitrust assumptions. Some of these include:

- Digital markets and new digital gatekeepers

- AI, Data, and Privacy concerns

- Market concentration concerns

- The rise of private equity

- Financial complexity and the financialization of firms

These have raised serious questions about what antitrust law is for. The overarching purpose, or normative goal, of antitrust law varies among jurisdictions and is increasingly contested, particularly in the US. Should the goal be: Anti-monopoly? Pro-competition? Consumer protection? Efficiency? Economic fairness? Or some combination of these, or other, goals? It is now widely accepted that competition policy – both its aims and its enforcement – has wider societal impacts beyond competition, including effects on democracy, economic inequality, growth and innovation, racial and gender imbalances, privacy, geopolitical implications and more. Its effects on the environment can also no longer be ignored.

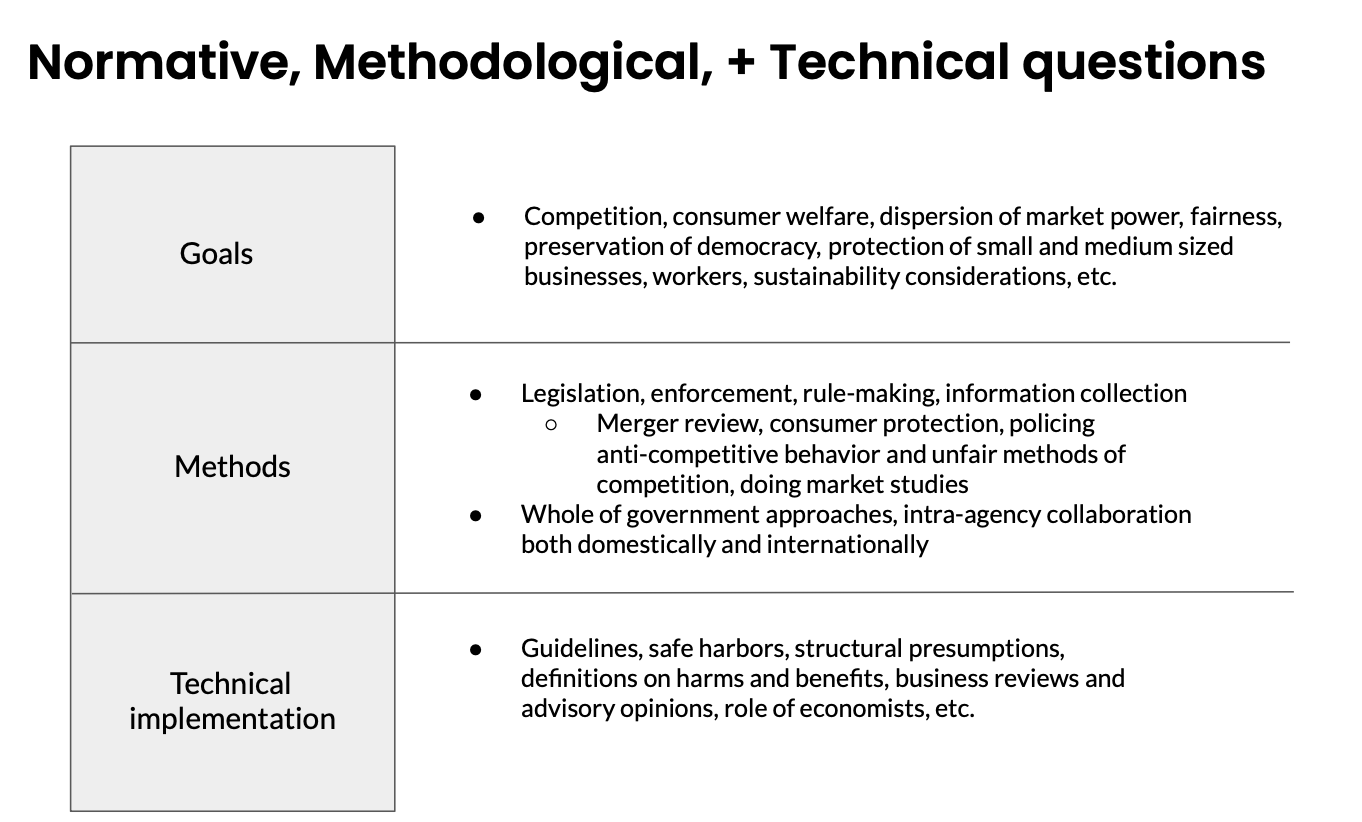

Across all jurisdictions, ideologies diverge on both the normative goals of competition law and policy, especially with respect to sustainability goals, as well as on the methods and technical approaches to achieve those goals.

In the US, the challenge is more complex for many reasons, including that antitrust is enforced at both the state and federal level and across multiple federal agencies. Within the past year, this fragmentation has enabled antitrust language and concepts to be weaponized in a way that does not align with core legal realities.

The purpose of this report is to provoke and support engaged and informed conversation among policymakers, private firms, and the wider public around the appropriate competition policy framework which can support sustainable development broadly. It considers the range of inherent complexities and aims to chart a path forward in a thoughtful manner.

Ultimately, competition policy and its enforcement agencies are one component of a broad policy framework that shapes private sector activities and their alignment with, or contributions to, climate or other sustainability-related policy objectives. Incentivizing private actors to align their practices with sustainability and climate goals will require policies and regulations throughout the economy. Antitrust policies and agencies should be a coherent part of this robust policy framework.

Read the full report here.